Deadly Gaps 2025

Impact of aid cuts

8th Global Fund replenishment

Read below to learn about the impact of the monumental aid funding cuts in 2025.

This work was collated by Dr Animesh Sinha (MSF and UKAPTB Research Lead)

The Global Fund

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, or Global Fund for short, plays a fundamental role in financing the fight against HIV, TB and malaria, particularly in countries where domestic funding capacity is limited and with fragile health systems.

The 2025 Global Fund replenishment (grant cycle; GC8) is taking place during a moment of extreme global instability.

Economic uncertainty, shifting donor commitments, and a retreat from multilateralism are threatening decades of progress in global health.

These pressures are compounded by intersecting crises - climate change, growing political conservatism, and increasingly complex and protracted conflicts - that are disproportionately affecting low- and middle-income countries

Global financing consistently falling short

©Prem Hessenkamp/India

Despite being the world’s deadliest infectious disease with 1.25 million deaths in 2023, TB has long been neglected in global health financing and continues to receive far less funding than HIV and malaria. As in the previous ten years, 80% of the spending on TB services in 2023 was from domestic sources.

Global Fund and the USAID were the two major donors of TB in 2024.

USAID provided $406 million in 2024 for TB global efforts, supporting the needs in 24 priority countries which are mainly in sub-Saharan Africa, South Asia, and Southeast Asia. The focus was on preventing, detecting, and treating TB, including drug-resistant TB, as well as research and development.

In 2022, the Global Fund accounted for 75% of all international donor funding for TB programmes, underscoring its essential role in the fight against the disease.

Yet even with this contribution, TB remains severely underfunded, with global financing falling short of the commitments needed to meet the WHO’s End TB targets.

TB Trends

The TB incidence rate, which is the new cases per 100,000 population per year, is estimated to have increased by 4.6% between 2020 and 2023, reversing declines of about 2% per year between 2010 and 2020.

Worldwide, an estimated 10.8 million people developed TB in 2023, up from best estimates of 10.7 million in 2022, 10.4 million in 2021 and 10 million in 2020.

A return to the pre-pandemic downward trend has not yet been seen. Without urgent action to close this funding gap, millions will continue to miss out on timely diagnosis and treatment, and the global TB response will continue to fall behind.

The Global Fund investment case

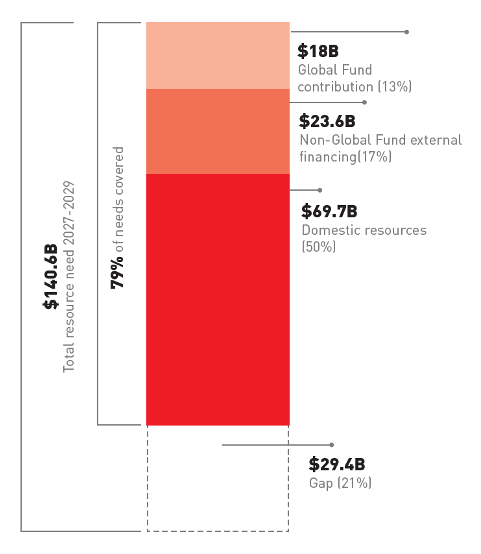

Between 2027 and 2029, the Global Fund estimates that US$140.6 billion will be required to combat HIV, TB and malaria, an 8% increase from the $130.2 billion projected in the last replenishment.

Achieving this target is expected to save 23 million lives and avert 400 million cases across the three diseases.

Yet, despite this growing need, the Global Fund’s contribution remains fixed at $18 billion, while governments are expected to take on an even greater share of health financing.

Domestic contributions are projected to rise by 19% from $58.6 billion in 2024-2026 to $69.7 billion in 2027-2029.

The investment case proposed for the eighth replenishment, by the Global Funds own admission is requesting less than the minimum to meet all needs of addressing HIV, TB and malaria.

Even before factoring in dramatically shifting donor priorities, Global Fund projections indicate a 21% funding gap.

The expectation that national governments will close this shortfall is detached from economic realities.

While domestic contributions are assumed to grow by 23%, the questions remain: where will this money come from, and more critically, who will be left behind?

Bilateral donors will not meet deficits

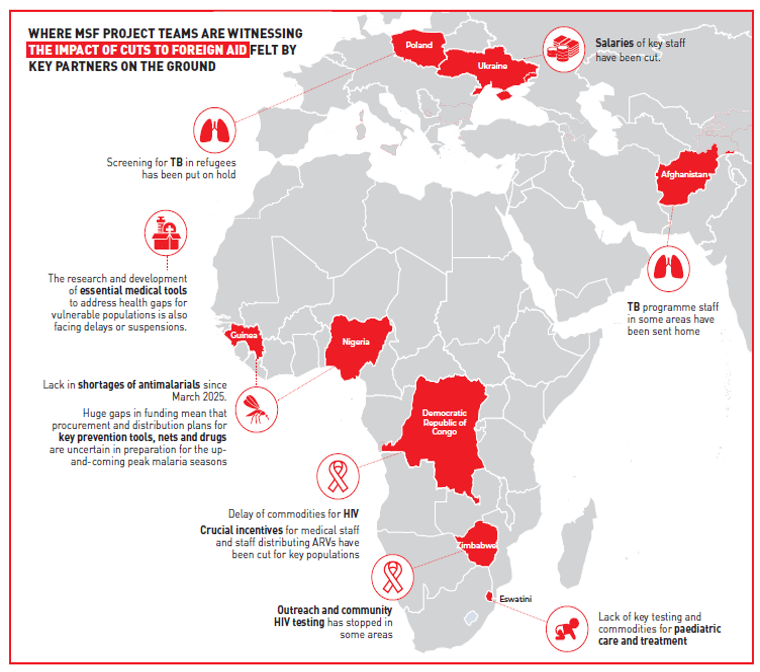

The global health financing landscape is entering a period of acute uncertainty, with potentially devastating consequences for TB, HIV, and malaria programmes. The most immediate and alarming threat comes from the US, where proposed budget cuts place PEPFAR, PMI and the TB bilateral program managed by USAID in jeopardy.

While the impacts and magnitude of the cuts to US foreign aid remain deeply uncertain, one thing is clear: a prolonged suspension or reduction of U.S. funding would cripple the availability of diagnostics and treatment for millions. Nowhere would this be more devastating than across Africa, especially the Sahel, where many national health programmes are sustained almost entirely through external financing from the Global Fund, PEPFAR, USAID and PMI.

The future of PMI, PEPFAR and TB bilateral programme remains uncertain. It is not only the cuts themselves that are damaging; the uncertainty about what lies ahead, whether funding will continue, for how long, and at what scale, is already destabilising national responses. Programme planning has stalled, procurement cycles are in disarray, and governments and implementing partners are left unable to make critical decisions.

The sheer scale and reach of U.S. global health support means that no other donor is positioned to fill the gaps left by a retreat of this magnitude. The overnight dismantling of US foreign aid has the potential to disrupt and push fragile health systems to the brink, reversing decades of gains and triggering a humanitarian catastrophe.

Domestic resources will not meet deficits

Already in the assumptions to determine the amount asked for in the investment case, the reliance on Domestic Resource Mobilisation (DRM) is unrealistically high. Within the investment case, financial sustainability scenarios and co-financing projections might be over-estimated. This high expectation will turn into a bigger gap than initially estimated.

Overall DRM for health is expected not to be increasing, mainly because of downward trend in economic growth and specific strains on the countries’ economy, such as (a combination of) conflict, food and epidemic crises, drought, inflation and devaluation, and price hikes.

Many LMICs already face weak tax bases, high debt burdens, and shrinking fiscal space. The World Bank estimates that 41 countries face the prospect of lower real per capita government spending in 2027 than in 2019, while another 69 countries risk seeing stagnation in 2027 compared to 2019 levels.

Health expenditure is outcompeted by debt repayments in highly indebted countries. Even countries classified as middle-income face shrinking budgets for public services and health. For instance, Pakistan allocates alarmingly low levels of government expenditure to health. A country’s classification as Low-, Middle-, or High Income is not adequately reflecting the fiscal space for health, the current health challenges, nor the population’s poverty rates.

Patients should not pay the price for funding deficit

While public DRM is often presented as a path to sustainability, it is important to recognise that in many countries, an increased burden shifted on “domestic resources” often comes with a hike in out-of-pocket (OoP) payments by people themselves. The proportion of OoPs in health expenditure has been consistently rising, especially in low-income countries, where OoP is the most important source of health financing

Efforts to expand care through public-private partnerships have shown mixed results. In Pakistan, the Global Fund has prioritised engagement with private providers for TB detection, as more than 80% of patients first seek care in the private sector. However, these private facilities often lie outside the National TB Program’s network and charge consultation fees, which limit access for poorer or rural patients. Without parallel investments in the public sector and clear accountability mechanisms, the expansion of private-sector engagement risks reinforcing existing inequalities in access and quality.

This high dependence on OoP spending creates barriers to accessing essential healthcare, particularly for the 73.5% of the population who live below the poverty line. In DRC 44% of health costs are covered by private domestic spending, 37% of which is through out-of-pocket (OoP) payments2

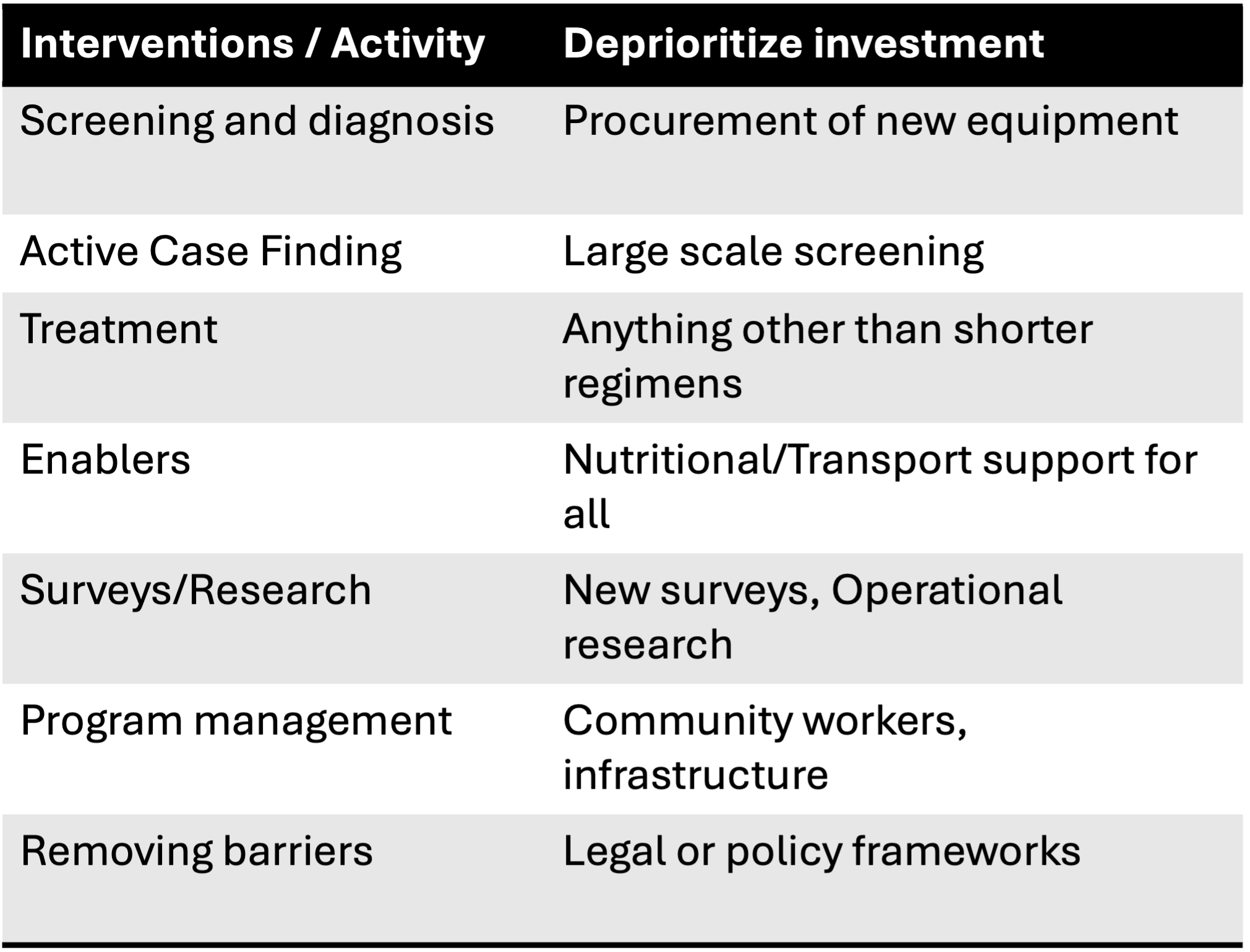

GC7 reprioritisation

During its last board meeting of May 2025, the Global Fund announced a deallocation process for the current grants 2024-2026, in response to the ongoing uncertainty in the funding landscape of bilateral and multilateral health programs, including GF.

As a consequence, Global Fund is asking each Country (through the Principial recipients and the Country Coordinating Mechanisms (CCM’s) ) to review the HIV, TB & Malaria grants in order to deprioritise (to “pause”) not essential interventions.

Other de-prioritatisation for HIV such as Procurement of new x-ray machines, Procurement of C reactive protein, IGRA and skin tests for screening, are likely to impact TB in PLHIV.

Example of Belarus where 1/3 of new cases and 2/3 of re-treatment cases. with stopped funding for ongoing research and no funding for screening activities.

People facing extra neglect and vulnerability

Populations affected by extreme weather events, conflict and displacement remain among the most neglected in the global response to HIV, TB and malaria. The situation in Sudan exemplifies this situation. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 70–80% of health facilities in Sudan are not functioning in the most-affected conflict areas, leaving millions without access to basic medical care and, needing to look elsewhere for care and adding to one of the largest displacement crises in recent history

Key populations, including men who have sex with men, transgender people, sex workers and people who use drugs, face disproportionately high HIV burdens compared to the general population. Key populations cannot be treated as optional in national strategies - they are essential to the success of the HIV, and very much linked with the TB response.

Many service gaps are impacting children, and without additional resources for better tools and approaches, children’s lives are at risk. Paediatric TB remains one of the most persistently neglected areas in the global TB response.

Potential mitigation measures

The investment case proposed for the 8th replenishment, by the Global Funds own admission is requesting less than the minimum to meet all needs in addressing HIV, TB and malaria.

Analysing the key gaps and unmet needs in current Global Fund grants should start with a review of the updated Prioritized Above Allocation Request (PAAR) and Unfunded Quality Demand (UQD) registers. In these, the unfunded high-quality interventions that were dropped during grant-making are reflected.

People facing specific and worse vulnerability are most at risk of service gaps and interruption of interventions. These include key populations, people in crisis including refugees and displaced people, those most at risk of dying rapidly due to severe illness, and children. Funding should focus on concrete, effective support to reduce mortality and morbidity risks, to protect them from exclusion from care, neglect and abuse.

In times of funding cuts or shortfalls, key strategies might suffer a loss of financial support, undermining effectiveness, coverage and efficiency reaching the needed results. This must be avoided at all costs, as it threatens the most effective use of available funding and will further risk the derailing of achievements and progress of the response against HIV, TB and malaria.

Health systems funding should prioritise those interventions that have a direct impact on patient and health benefits, protecting them from disruptions in treatment, care and prevention. This includes sufficient availability of essential medical supplies, provided free of charge to people.

With health budgets under strain, obtaining lower prices for essential products will be key, and the Global Fund should increase its role in negotiation and market-shaping.

The focus ahead

The United Kingdom, co-hosting the Global Fund replenishment alongside South Africa, has added to the uncertainty.

In February, the UK Prime Minister announced further reductions in aid spending, cutting the target from 0.5% of gross national income (GNI) to 0.3% by 2027 in favour of increased defence expenditures.

Other European nations are following suit, retreating from their financial commitments to global health, with France making cuts to Overseas Development Aid (ODA) of 35%, the Netherlands of 25% and Belgium of 25%.

This signals a broader shift in donor priorities, where global health is increasingly seen as a secondary concern rather than a shared responsibility.

This fragility is compounded by a wider retreat from global solidarity.

Previous commitments of fair financing to official development assistance (ODA) and global health are being abandoned.

Across donor governments ODA is being scaled back or redirected, and support for multilateralism is weakening.

If these trends continue, the hard-won gains of the past two decades could unravel, driven not by the failure of tools or strategies, but by the erosion of the financing that sustains them.

This page has been created thanks to Dr Animesh Sinha and Médecins Sans Frontières

To read the full report:

Follow the QR Code